Bangladesh’s Sea Boundary dispute with India and Myanmar before the International Tribunal

Since Bangladesh’s birth in 1971, the importance of the sea and its resources has been recognised. By 1974, Bangladesh is the only country in South Asia to enact a maritime law, called the Territorial Waters and Maritime Zones Act (XXVI of 1974).

Under the law, Bangladesh has claimed 12 territorial sea, another 188 miles of exclusive economic zone and continental shelf to “the outer limits of the continental margin on the ocean basin or abyssal floor” (another 150 miles beyond exclusive economic zone). In 1976, India and in 1977, Myanmar enacted similar laws.

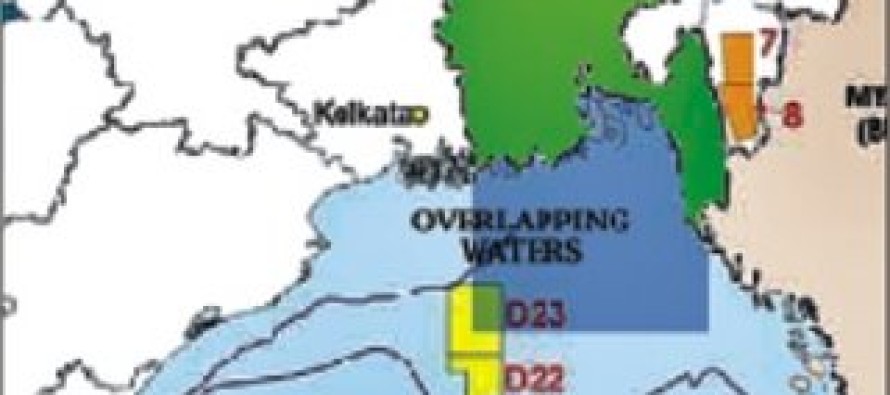

To put simply, Bangladesh’s claim of maritime zones consist of two parallel lines extending southward on the meridians of the longitude from baselines corresponding to its coastline up to the outer limits of continental shelf.

The urgency in delimitation of maritime boundary for Bangladesh with neighbours- India and Myanmar- partly because Bangladesh cannot explore and exploit off-shore areas due to overlapping claims of India and Myanmar, and partly because strong prospects for gas/oil in the off-shore areas exist, coupled with the rising domestic demand for oil/gas for generation of power to make it a middle-income nation by 2021.

Furthermore, the most remarkable progress in off-shore technologies during the last 15 years is the three fold increase in the maximum operational depth of off-shore rigs which has opened up thousands of square miles in the Bay of Bengal.

Bilateral negotiations commenced in 1974 with India and Myanmar. After a lapse of 26 years bilateral negotiations with India resumed in September 2008 and in March 2009. The impasse remained.

After a lapse of 22 years negotiations resumed with Myanmar in November 2008 and the last one took place in March 2010. The discussions did not yield any positive result.

Bangladesh, India and Myanmar ratified the 1982 UNCLOS (UN Convention on the Law of the Sea). Bangladesh ratified in July 2001, India in 1995 and Myanmar in 1996. They accept the rules of UNCLOS and laws of international law on the subject matter including the dispute settlement mechanism.

Article 287 of UNCLOS provides, among others, two procedures of dispute settlement:

• International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea established in accordance with Annex VI; (ITLOS)

• Arbitral Tribunal constituted in accordance with Annex VII;

The structure and procedure of ITLOS differs from that Arbitral Tribunal. The Tribunal consists of 21 independent elected judges and each party nominates one judge each.

The Arbitration Tribunal is composed of five arbitrators—three appointed by the President of the Tribunal and one each by the parties. Furthermore the procedure of ITLOS is likely to proceed more quickly than that of arbitration.

Bangladesh-Myanmar:

Given the impasse, Bangladesh had no other alternative but to refer the matter before the Tribunal on 14 December 2009 to which both Bangladesh and Myanmar accepted the jurisdiction of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS).

It is noted that initially Myanmar opted for arbitration but later reversed its decision in favour of ITLOS, because the parties reportedly could not reach a consensus on nominating the arbitrators to Tribunal.

During consultations held with the President of the Tribunal on 25 and 26 January 2010 on the premises of the Tribunal in Hamburg, Germany, the representatives of the parties agreed on the following time-limits for the filing of the written pleadings:

• 1 July 2010: Time-limit for the filing of the Memorial by Bangladesh;

• 1 December 2010: Time-limit for the filing of the Counter-Memorial by Myanmar.

They further agreed that the time-limits for the filing of pleadings should be as follows:

• 15 March 2011: Time-limit for the filing of the Reply by Bangladesh;

• 1 July 2011: Time-limit for the filing of the Rejoinder by Myanmar.

.The proceedings will begin by the end of the next year (2011). Ordinarily it takes 2 to 3 years and the decision is final.

Bangladesh-India:

India did not accept the jurisdiction of International Tribunal as Myanmar did and opted for Arbitration Tribunal under Annex VII.

On 8th October 2009, Bangladesh initiated arbitration proceedings against India. In February, 2010, the President of the Tribunal appointed three arbitrators- Tullio Treves of Italy, I.A. Shearer of Australia and Rudigar Wolfrum of Germany. (Tullio Treves and Ivan Anthony Shearer are ITLOS judges).

Bangladesh nominated Alan Vaughan Lowe, Q.C., a former professor of Oxford University and India nominated P. Sreenivasa Rao, former Legal Adviser of the External Affairs Ministry.

In May this year, the President of the Arbitral Tribunal called India and Bangladesh to attend a meeting to fix a time table of submission of their pleadings and rejoinders. It was decided as follows:

• Bangladesh is to lodge its statement of claim by May 2011

• India will respond by May 2012.

The decision of the proceedings may take five years.

Main issues before the Tribunal:

The first issue is that the proceedings will address important equity and equidistance method in defining exclusive economic zone in the Bay of Bengal.

Given the concave coast of Bangladesh and also taking into account of Bangladesh position as lateral /adjacent states, with India and Myanmar (as opposed to India and Sri Lanka), Bangladesh strongly argues that equidistance method is not suitable as a starting point to delimit maritime boundary in the Bay of Bengal.

Much of the continental shelf claimed by Bangladesh can be argued to be the deposit of silt through the rivers through Bangladesh, carrying silt (1.8-2 billion tons of silt annually) forming the continental shelf which is arguably a natural prolongation of the landmass of Bangladesh in the southward direction.

Bangladesh further argues that if India and Myanmar insist on equidistance method, Bangladesh will be affected by effects of “cut-off “ that will turn a coastal country into a “sea-locked” nation without any opening to high seas and will not be able to claim additional 150 miles of continental shelf.

The interpretation of customary international law of maritime delimitation as embodied in the 1969 ICJ judgment and Articles 74 and 83 of UNCLOS provide strength, in my view, to Bangladesh’s above argument and that equity has emerged as integral part of law in maritime delimitation. States may take recourse to various factors to achieve an equitable solution.

In 1969, the International Court of Justice ordered the parties ( Denmark, Germany and Netherlands) to negotiate the boundary by application of equitable principles so as to avoid the “cut-off” for Germany that would result from equidistance method.

The Court stated: “Delimitation is to be effected by agreement taking into account all the relevant circumstances…including general configuration of the coast of the parties, physical and geological structure”.

It is noted that the India’s claim in the Bay of Bengal constitutes about 5-7% of their total maritime zone and Myanmar’s claim could be no more than 15% of its total claim while Bangladesh’s stake is 100% in the Bay of Bengal.

A corollary issue before the Tribunal is whether the baselines drawn by Bangladesh, India and Myanmar are consistent with the provisions of UNCLOS (Article 7). While Bangladesh objected to Indian and Myanmar’s description of baselines, they also do not accept the Bangladesh’s baseline.

Meanwhile lodgment of proceedings with the International Tribunal and Arbitration does not preclude bilateral discussions with India and Myanmar.

The reference to the UNCLOS dispute machinery is a positive development in stark contrast to the stagnation of maritime talks during the period of more than two decades between Bangladesh and its neighbours.

The decision of the Tribunals will provide legal precedents that affect maritime boundary elsewhere.

By Barrister Harun ur Rashid

Former Bangladesh Ambassador to the UN, Geneva